Where does Curly-leaf Pondweed (CLP) grow naturally, and how did it get here?

CLP is native to Europe and Asia. It spread to North America through boats and the aquarium trade. It moves from lake to lake in Wisconsin via boaters, especially through its overwintering buds, called turions.

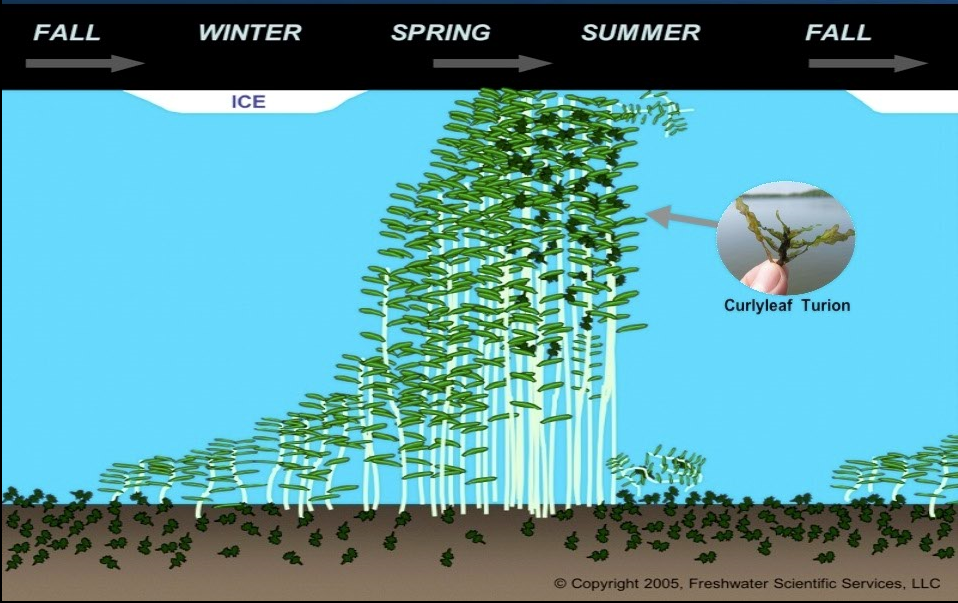

An interesting life history:

CLP is usually the first plant in lakes to appear in the spring. This is because it starts growing during the winter under the ice! CLP matures by early summer, and begins to produce

turions, which are the overwintering buds CLP uses to reproduce.

The turions fall off the plant around July 4th, sinking into the sediment below. These turions sprout into new plants during the winter. Turions may sprout later that same year, or they may sit in the sediment for up to 7 years before sprouting. This makes treating CLP particularly difficult, as we can never be sure of the turion seedbank within the sediment. CLP treatment must be a vigilant, multi-year approach.

How do I identify CLP?

The leaves of CLP are finely serrated, giving it a jagged, tooth-like appearance. This also causes the plant to feel more coarse. When you hold a single leaf of CLP, it looks similar to a lasagna noodle (hence “curly leaf” pondweed).

CLP is most often confused with clasping leaf pondweed, which does not have serrated leaf edges, and also has leaves that “clasp” around the stem.

If you suspect you have found CLP in your lake, please

contact our Woods and Water Team for verification.

How does CLP impact a Wisconsin lake?

CLP out-competes native plants in water bodies, and can grow so quickly that it can cause surface matting. This interferes with recreational usage of lakes. The matted CLP also blocks sunlight from native plants. Once the CLP dies off in mid-summer, little vegetation is left where CLP was growing, thereby removing habitat for other critters that live in the lake.

What can be done once CLP enters a water body?

Because CLP has a unique life history, and can potentially build up a large "seed bank" of turions, treatment of CLP is often a multi-year process. Some chemicals, such as endothall, have successfully depleted CLP populations. However, these chemicals require a permit, can be expensive, and are non-selective (meaning they can potentially kill any plant that comes in contact with the chemical).

If CLP populations are smaller, hand-harvesting of CLP has shown promising potential. Your lake group could hire professional divers, or could have volunteers hand-pull CLP. Please

contact the Woods and Water Team if you have any questions about CLP hand removal.

additional resources

Manitowish Waters Lakes Association

Wisconsin DNR Aquatic Invasive Species

Great Lakes Indian Fish & Wildlife Commission (GLIFWC) Invasive Species Area Maps

books (available for loan)

Lake Plants You Should Know- A Visual Field Guide, University of Wisconsin- Extension

Aquatic Plants of the Upper Midwest- A Photographic Field Guide To Our Underwater Forests, Paul Skawinski

Through the Looking Glass- A Field Guide to Aquatic Plants, Susan Borman, Robert Korth, and Jo Temte.

Saving Our Lakes and Streams, James A. Brakken